Back to your roots

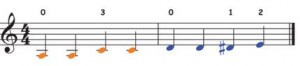

Here is an idea for an activity that I often do with young beginner guitarists – sometimes in the very first lesson. It involves making a very simple accompaniment to London Bridge is Falling Down, with two open string notes played to a slow steady pulse. It is simple enough to do by ear, though it also makes a good introduction to reading the notes on the stave.

Here is an excerpt (it’s on p9 of Rainbow Guitar Book 1). Click on the image to see it full size:

If you teach this age group and you haven’t tried this sort of activity, then you should.

The tune can be sung or played by the teacher. It is easy, musical, and effective, and pupils enjoy the feeling of playing a familiar tune from Day One (the fact that they are accompanying, rather than playing the tune itself, does not seem to trouble them at all).

As well as being fun and motivating, this activity ticks a lot of boxes from the point of view of the instrumental teacher and music teacher. We are practising keeping a steady beat, making a steady clear sound on a single string, and counting. We are also experiencing the musical elements of pulse vs. rhythm, melody vs. harmony, and the whole notion of accompaniment. Not to mention that we are plugging straight into the harmonic “deep structure” of the tune (tonic and dominant).

A little later on, as the pupils move on to triple time, we might take a similar approach to “Molly Malone”. Again here is an excerpt (Rainbow Guitar Book 1, p10):

Single-note drone accompaniments are a great resource for any music teacher, and they work particularly well for a guitar teacher. Firstly because drones actually sound natural and right on the guitar (this is certainly not true of every instrument). Secondly because accompaniment is such an essential skill for all guitar players, and drones provide a way of getting into accompaniment long before the pupil can manage “proper” chords on the guitar.

Tick Tock

Another, slightly more advanced, idea for an accompaniment activity is to get the pupils to alternate two chord tones in a pattern. (Let’s assume now that the pupil has started to use the left hand, and can manage one or two fretted notes).

Here is an example from p15 of Rainbow Guitar Book 1 (again, just click on any of the images to see it full size):

“Sur le pont d’Avignon” has just two harmonies: tonic and dominant (G and D). By alternating two notes in each chord (in this case, root and fifth) we create a sense of constant movement – but because the notes are in patterns, the player can “think in bars” rather than “thinking note by note” – only having to make a change at the beginning of each bar. This is an essential point – and an important reason why accompaniment activities can be so motivating and work so well in lessons. Put very simply, when you play this sort of accompaniment, your brain is able to work more slowly than it does when playing melody. This can provide a little welcome respite. Look again at the example above, and think how much more information the brain has to process, and how many more decisions have to be taken, when playing the melody as opposed to the accompaniment.

Here is another example of an accompaniment using two notes from each chord, from p24 of Rainbow Guitar Book 2):

This one is more advanced rhythmically than the first, and more advanced for the plucking hand as well. Similar rhythmic patterns can be found in many contemporary rock and pop accompaniments.

For the guitar teacher there is one final piece of good news about working with two-note patterns such as the above: it makes the pupil aware of how notes can overlap (or not) and of how these different effects are achieved.

Don’t forget ostinatos

Ostinatos are another classic device for making accompaniments, and although they need not be confined to chord tones, they often act in a chordal way. They can suggest a chord, and move from one starting note to another in sync with the harmonies of a song or tune. For a young novice guitar pupil, playing ostinatos (or riffs) has the advantage that we mentioned in the last section, that pupils can get by without using too much brain power – grouping or chunking the notes together in the mind and only having to change the pattern once every few bars.

Here is a time-honoured riff which pupils enjoy enormously. It appears in Rainbow Guitar Book 2 p22. It can be easily moved from string to string, perhaps to make a classic 12-bar blues pattern starting on open A, D and E bass notes:

From a guitar teacher’s point of view, there is really nothing not to like about riffs. Short, simple, real, memorisable … and they give great left hand finger practice (the one above is great for getting the first finger to reach over to the bass strings).

Broken chords

The two-note patterns discussed above can be developed into patterns with three or four strings, and more different string combinations. This is more challenging for both hands than the examples above. There are many such broken-chord patterns in Rainbow Guitar Book 2, using plenty of open strings and often not requiring more than one fretting finger at a time.

Here is an excerpt from “Ring Finger Blues” (Rainbow Guitar Book 2 p 29):

In conclusion …

I do hope I have convinced you (if you were not already convinced) that ALL guitar pupils, whatever their age or level, benefit from some accompaniment work in lessons. Here are some of the most important reasons why:

- This kind of work gives immediate hands-on experience of important elements of music (for example pulse vs. rhythm; melody vs. harmony; texture; balance) which do not always come to the fore when learning “melody only”.

- It also brings out some of the social aspects of music making (I take one role, you take another).

- Focussing on harmony rather than melody can give the overworked pupil a little respite. The brain has to process less information and make fewer choices. A melody may have many notes, which may move quite quickly and in all sorts of rhythmic shapes. Playing such a melody requires the brain to work constantly, processing lots of information and making a rapid stream of decisions and choices. The same piece probably uses a relatively small number of harmonies, and the harmonic rhythm is likely to be slower and simpler than that of the melody.

- Chords, by their nature, lend themselves to an explorative approach to music learning. They give the pupil quick access to deep musical structures – structures which the melody player may simply not be aware of, or have time to think about. This is why chord work so often, in and of itself, leads to pupils making up their own songs and progressions. Chord work is enormously liberating and empowering.

And lastly one more bit of good news: if you teach the Seven-Year-Old Guitarist who is the subject of this blog series, you have the great advantage that 7-year-olds have more open minds than many older pupils. When it comes to chords, they are happy to have things broken down into chunks and tidbits, they are less likely to want to overstretch themselves and less likely to want to know everything all at once. Enjoy it while it lasts … 🙂